Jameson Raid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched

After the

After the

As part of the planning, a force had been placed at Pitsani, on the border of the Transvaal, by the order of Rhodes so as to be able to quickly offer support to the Uitlanders in the uprising. The force was placed under the control of

As part of the planning, a force had been placed at Pitsani, on the border of the Transvaal, by the order of Rhodes so as to be able to quickly offer support to the Uitlanders in the uprising. The force was placed under the control of  Although Jameson's men had cut the telegraph wires to Cape Town, they had failed to cut the telegraph wires to Pretoria (cutting a fence by mistake). Accordingly, news of his incursion quickly reached Pretoria and Jameson's armed column was tracked by Transvaal forces from the moment that it crossed the border. The Jameson armed column first encountered resistance very early on 1 January when there was a very brief exchange of fire with a Boer outpost. Around noon the Jameson armed column was around twenty miles further on, at

Although Jameson's men had cut the telegraph wires to Cape Town, they had failed to cut the telegraph wires to Pretoria (cutting a fence by mistake). Accordingly, news of his incursion quickly reached Pretoria and Jameson's armed column was tracked by Transvaal forces from the moment that it crossed the border. The Jameson armed column first encountered resistance very early on 1 January when there was a very brief exchange of fire with a Boer outpost. Around noon the Jameson armed column was around twenty miles further on, at

online

* A revision of * * Onselen, Charles van. ''The Cowboy Capitalist: John Hays Hammond, the American West, and the Jameson Raid''(University of Virginia Press, 2018), * * * * * {{Authority control 1895 in South Africa 1896 in South Africa 19th century in Africa African resistance to colonialism Conflicts in 1895 Conflicts in 1896 December 1895 events History of Pretoria History of the British Empire January 1896 events Military history of South Africa Military raids South Africa–United Kingdom relations Wars involving Botswana Wars involving the British South Africa Company Wars involving the South African Republic

raid

Raid, RAID or Raids may refer to:

Attack

* Raid (military), a sudden attack behind the enemy's lines without the intention of holding ground

* Corporate raid, a type of hostile takeover in business

* Panty raid, a prankish raid by male college ...

against the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

(commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Baronet, (9 February 1853 – 26 November 1917), was a British colonial politician, who was best known for his involvement in the ill-fated Jameson Raid.

Early life and family

He was born on 9 February 1853, of ...

, under the employment of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

. It involved 500 British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

police launched from Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

over the New Year weekend of 1895–96. Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904) was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and President of the South African Republic (or ...

, whom Rhodes had a great personal hatred towards, was president of the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

at the time. The raid was intended to trigger an uprising by the primarily British expatriate workers (known as Uitlander

Uitlander, Afrikaans for "foreigner" (lit. "outlander"), was a foreign (mainly British) migrant worker during the Witwatersrand Gold Rush in the independent Transvaal Republic following the discovery of gold in 1886. The limited rights granted to ...

s) in the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

but failed to do so. The workers were called the Johannesburg conspirators. They were expected to recruit an army and prepare for an insurrection; however, the raid was ineffective, and no uprising took place. The results included embarrassment of the British government; the replacement of Cecil Rhodes as prime minister of the Cape Colony; and the strengthening of Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

dominance of the Transvaal and its gold mines. The raid was a contributory cause of the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902).

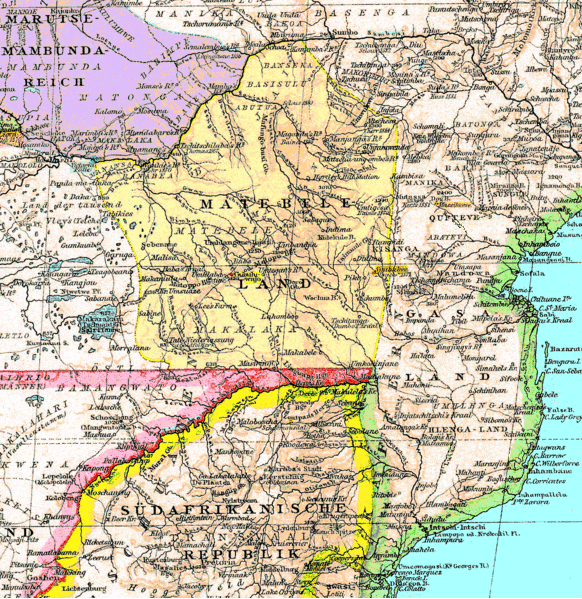

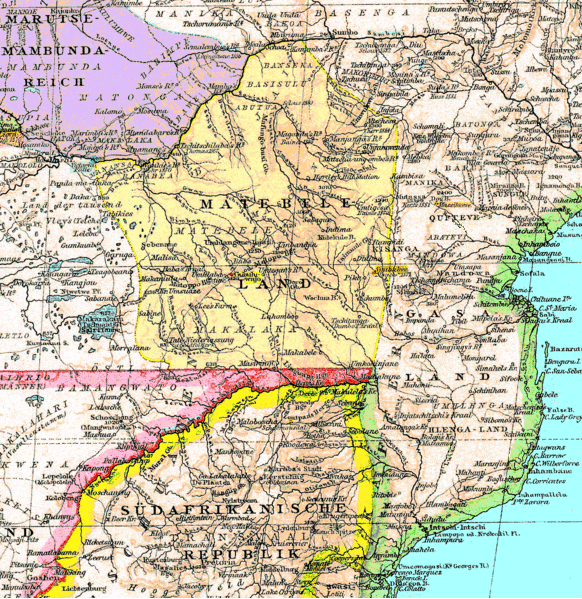

Background

What later became South Africa was not a single, united nation during the late nineteenth century. The territory had four distinct entities: the two British colonies ofCape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

and Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

; and the two Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

republics of the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

and the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

, more commonly referred to as the Transvaal.

Foundation of the colonies and republics

The Cape, more specifically the small area around present dayCape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, was the first part of South Africa to be settled by Europeans; the first immigrants arrived in 1652. These settlers were transported by, and long remained under the control of, the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

.

Gradual consolidation and eastward expansion took place over the next 150 years; however, by the beginning of the nineteenth century, Dutch power had substantially waned. In 1806, Great Britain took over the Cape to prevent the territory falling to Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and to secure control over the trade routes to the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

.

Antipathy towards British control and the introduction of new systems and institutions grew amongst a substantial portion of the Boer community. One of the primary causes of friction was policy of the British authorities towards slavery in South Africa

Slavery in South Africa existed from 1653 in the Dutch Cape Colony until the abolition of slavery in the British Cape Colony on 1 January 1834. This followed the British banning the trade of slaves between colonies in 1807, with their emancip ...

. In 1828, legislation passed by the British parliament guaranteed equal treatment under the law for all, regardless of race. In 1830, a new ordinance imposed heavy penalties for harsh treatment of slaves. The measure was controversial among some of the population, and in 1834, the government abolished slavery in the British Empire altogether. The Boers opposed the changes, as they believed they needed enslaved labor to make their farms work. They believed the slaveholders were compensated too little upon emancipation. They were also suspicious of how the government paid for compensation. This resentment culminated in the en-masse migration of substantial numbers of the Boers into the hitherto unexplored frontier, to get beyond the control of British rule. The migration became known as the Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyon ...

.

This anti-British feeling was by no means universal: in the Western Cape, few Boers felt compelled to move. The Trekboers

The Trekboers ( af, Trekboere) were nomadic pastoralists descended from European settlers on the frontiers of the Dutch Cape Colony in Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the C ...

, frontier farmers in the East who had been at the front of the colony's eastward expansion, were the ones who elected to trek further afield. These emigrants, or Voortrekkers as they became known, first moved east into the territory later known as Natal. In 1839, they founded the Natalia Republic

The Natalia Republic was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 after a Voortrekker victory against the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River. The area was previously named ''Natália'' by Portuguese sailors, due to its discovery on Christma ...

as a new homeland for the Boers. Other Voortrekker parties moved northwards, settling beyond the Orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

*Orange (colour), from the color of an orange, occurs between red and yellow in the visible spectrum

* ...

and Vaal

The Vaal River ( ; Khoemana: ) is the largest tributary of the Orange River in South Africa. The river has its source near Breyten in Mpumalanga province, east of Johannesburg and about north of Ermelo and only about from the Indian Ocean. ...

rivers.

Reluctant to have British subjects moving beyond its control, Britain annexed the Natalia Republic in 1843, which became the Crown colony of Natal. After 1843, British government policy turned strongly against further expansion in South Africa. Although there were some abortive attempts to annex the territories to the north, Britain recognised their independence by the Sand River Convention

The Sand River Convention ( af, Sandrivierkonvensie) of 17 January 1852 was a convention whereby the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River.

Background

The conven ...

of 1852 and the Orange River Convention

The Orange River Convention (sometimes also called the Bloemfontein Convention) was a convention whereby the British formally recognised the independence of the Boers in the area between the Orange and Vaal rivers, which had previously been know ...

of 1854, for the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

, respectively.

After the

After the First Anglo-Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

, Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

's government restored the Transvaal's independence in 1884 by signing the London Convention. No one knew there would be the discovery of the colossal gold deposits of the Witwatersrand

The Witwatersrand () (locally the Rand or, less commonly, the Reef) is a , north-facing scarp in South Africa. It consists of a hard, erosion-resistant quartzite metamorphic rock, over which several north-flowing rivers form waterfalls, which ...

two years later by Jan Gerrit Bantjes (1843-1911).

Economics

Despite the political divisions, the four territories were strongly linked. Each was populated by European-African emigrants from the Cape; many citizens had relatives or friends in other territories. As the largest and longest established state inSouthern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number of ...

, the Cape was economically, culturally, and socially dominant: by comparison, the population of Natal and the two Boer republics were mostly pastoralist, subsistence farmers.

The fairly simple agricultural dynamic was upset in 1870, when vast diamond fields were discovered in Griqualand West

Griqualand West is an area of central South Africa with an area of 40,000 km2 that now forms part of the Northern Cape Province. It was inhabited by the Griqua people – a semi-nomadic, Afrikaans-speaking nation of mixed-race origin, wh ...

, around modern-day Kimberley. Although the territory had historically come under the authority of the Orange Free State, the Cape government, with the assistance of the British government, annexed the area, taking control of its vast mineral wealth.

Discovery of gold

In June 1884, Jan Gerrit Bantjes (1843–1914) discovered signs of gold at Vogelstruisfontein (the first gold sold directly to Cecil Rhodes at Bantjes's camp for £3,000) followed in September by the Struben brothers at Wilgespruit near Roodepoort which started the Witwatersrand Gold Rush and modern-day Johannesburg. The first gold mines of the Witwatersrand were the Bantjes Consolidated Mines. By 1886 it was clear that there were massive deposits of gold in the main reef. The huge inflow of ''Uitlander

Uitlander, Afrikaans for "foreigner" (lit. "outlander"), was a foreign (mainly British) migrant worker during the Witwatersrand Gold Rush in the independent Transvaal Republic following the discovery of gold in 1886. The limited rights granted to ...

s'' (foreigners), mainly from Britain, had come to the region in search of employment and fortune. The discovery of gold made the Transvaal overnight the richest and potentially the most powerful nation in southern Africa, but it attracted so many Uitlanders (in 1896 approximately 60,000) that they quickly outnumbered the Boers (approximately 30,000 white male Boers).

Fearful of the Transvaal's losing independence and becoming a British colony, the Boer government adopted policies of protectionism and exclusion, to include restrictions requiring Uitlanders to be resident for at least four years in the Transvaal to obtain the franchise, or right to vote. They heavily taxed the growing gold mining industry which was predominantly British and American. Due to this taxation, the Uitlanders became increasingly resentful and aggrieved about the lack of representation. President Paul Kruger called a closed council, including Jan Gerritse Bantjes, to discuss the growing problem and it was decided to put a heavy tax on the sale of dynamite to non-Boer residents. Jan G. Bantjes, fluent in both spoken and written Dutch and English, was a close confidant of Paul Kruger with their link dating to the Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyon ...

days. Jan's father, Jan Gerritze Bantjes, had given Paul Kruger his elementary education during the trek and Jan Gerritse was part of his inner core of associates. This closed council would be the committee which set the Transvaal Republic on a collision course with Great Britain and the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 and which set German feelings toward Britain at boiling point by siding with the Boers. Because of this applied dynamite tax, considerable discontent and tensions began to rise. As Johannesburg was largely an Uitlander city, non-boer leaders there began to discuss the proposals for an insurrection.

Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

, Governor of the Cape, had a desire to incorporate the Transvaal and the Orange Free State in a federation under British control. Having combined his commercial mining interests with Alfred Beit

Alfred Beit (15 February 1853 – 16 July 1906) was a Anglo-German gold and diamond magnate in South Africa, and a major donor and profiteer of infrastructure development on the African continent. He also donated much money to university edu ...

to form the De Beers Mining Corporation, the two men also wanted to control the Johannesburg gold mining industry. They played a major role in fomenting Uitlander grievances.

Rhodes later told the journalist W.T. Stead that he feared that a Uitlander rebellion would cause trouble for Britain if not controlled by him:

In mid-1895, Rhodes planned a raid by an armed column from Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

, the British colony to the north, to support an uprising of Uitlanders with the goal of taking control. The raid soon ran into difficulties, beginning with hesitation by the Uitlander leaders.

Drifts Crisis

In September and October 1895, a dispute between the Transvaal and Cape Colony governments arose over Boer trade protectionism. The Cape Colony had refused to pay the high rates charged by the Transvaal government for use of the Transvaal portion of the railway line to Johannesburg, instead opting to send its goods by wagon train directly across theVaal River

The Vaal River ( ; Khoemana: ) is the largest tributary of the Orange River in South Africa. The river has its source near Breyten in Mpumalanga province, east of Johannesburg and about north of Ermelo and only about from the Indian Ocean. ...

, over a set of fords (known as 'drifts' in South Africa). Transvaal president Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904) was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and President of the South African Republic (or ...

responded by closing the drifts, angering the Cape Colony government. While Transvaal eventually relented, relations between the nation and Cape Colony remained strained.

Jameson force and the initiation of the raid

As part of the planning, a force had been placed at Pitsani, on the border of the Transvaal, by the order of Rhodes so as to be able to quickly offer support to the Uitlanders in the uprising. The force was placed under the control of

As part of the planning, a force had been placed at Pitsani, on the border of the Transvaal, by the order of Rhodes so as to be able to quickly offer support to the Uitlanders in the uprising. The force was placed under the control of Leander Starr Jameson

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Baronet, (9 February 1853 – 26 November 1917), was a British colonial politician, who was best known for his involvement in the ill-fated Jameson Raid.

Early life and family

He was born on 9 February 1853, of ...

, the Administrator General of the Chartered Company (of which Cecil Rhodes was the Chairman) for Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi r ...

. Among the other commanders was Raleigh Grey

Sir Raleigh Grey (24 March 1860 – 10 January 1936) was a British coloniser of Southern Rhodesia who played an important part in the early government of the colony.

Early career

Grey, the great-grandson of 1st Earl Grey, was educated at Du ...

. The force was around 600 men, about 400 from the Matabeleland Mounted Police and the remainder other volunteers. It was equipped with rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

s, somewhere between eight and sixteen Maxim machine gun

The Maxim gun is a recoil-operated machine gun invented in 1884 by Hiram Stevens Maxim. It was the first fully automatic machine gun in the world.

The Maxim gun has been called "the weapon most associated with imperial conquest" by historian ...

s, and between three and eleven light artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

pieces.

The plan was that Johannesburg would revolt and seize the Boer armoury in Pretoria. Jameson and his force would dash across the border to Johannesburg to "restore order" and with control of Johannesburg would control the gold fields.

However, while Jameson waited for the insurrection to begin, differences arose within the Reform Committee and between Johannesburg Uitlander reformers regarding the form of government to be adopted after the coup. At a point, certain reformers contacted Jameson to inform him of the difficulties and advised him to stand down. Jameson, with 600 restless men and other pressures, became frustrated by the delays and, believing that he could spur the reluctant Johannesburg reformers to act, decided to go ahead. He sent a telegram on 28 December 1895 to Rhodes warning him of his intentions - "Unless I hear definitely to the contrary, shall leave to-morrow evening" - and on the very next day sent a further message, "Shall leave to-night for the Transvaal". However, the transmission of the first telegram was delayed, so that both arrived at the same time on the morning of 29 December, and by then Jameson's men had cut the telegraph wires and there was no way of recalling him.

On 29 December 1895, Jameson's armed column crossed into the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

and headed for Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

. They hoped that this would be a three-day dash to Johannesburg before the Boer commandos could mobilise, and would trigger an uprising by the Uitlanders.

The British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

, though sympathetic to the ultimate goals of the raid, realized it would be a mistake since the uitlanders were not supportive. He immediately tried to stop it, remarking that "if this succeeds it will ruin me. I'm going up to London to crush it". He rushed back to London and ordered Sir Hercules Robinson

Hercules George Robert Robinson, 1st Baron Rosmead, (19 December 1824 – 28 October 1897), was a British colonial administrator who became the 5th Governor of Hong Kong and subsequently, the 14th Governor of New South Wales, the first Gove ...

, governor-general of the Cape Colony, to repudiate the actions of Jameson and warned Rhodes that the company's charter would be in danger if it were discovered the Cape Prime Minister was involved in the raid. Chamberlain therefore instructed local British representatives to call on British colonists not to offer any aid to the raiders.

Although Jameson's men had cut the telegraph wires to Cape Town, they had failed to cut the telegraph wires to Pretoria (cutting a fence by mistake). Accordingly, news of his incursion quickly reached Pretoria and Jameson's armed column was tracked by Transvaal forces from the moment that it crossed the border. The Jameson armed column first encountered resistance very early on 1 January when there was a very brief exchange of fire with a Boer outpost. Around noon the Jameson armed column was around twenty miles further on, at

Although Jameson's men had cut the telegraph wires to Cape Town, they had failed to cut the telegraph wires to Pretoria (cutting a fence by mistake). Accordingly, news of his incursion quickly reached Pretoria and Jameson's armed column was tracked by Transvaal forces from the moment that it crossed the border. The Jameson armed column first encountered resistance very early on 1 January when there was a very brief exchange of fire with a Boer outpost. Around noon the Jameson armed column was around twenty miles further on, at Krugersdorp

Krugersdorp (Afrikaans for ''Kruger's Town'') is a mining city in the West Rand, Gauteng Province, South Africa founded in 1887 by Marthinus Pretorius. Following the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand, a need arose for a major town in the west ...

, where a small force of Boer soldiers had blocked the road to Johannesburg and dug in and prepared defensive positions. Jameson's force spent some hours exchanging fire with the Boers, losing several men and many horses in the skirmish. Towards evening the Jameson armed column withdrew and turned south-east attempting to flank the Boer force. The Boers tracked the move overnight and on 2 January, as the light improved, a substantial Boer force with some artillery was waiting for Jameson at Doornkop

Doornkop (literally "thorn hill") is a ridge and locality on the western outskirts of Soweto in the Gauteng Province, South Africa.

Battles

It is the spot where Dr Leander Starr Jameson was defeated on 2 January 1896 following the Jameson Raid ...

. The tired raiders initially exchanged fire with the Boers, losing around thirty men before Jameson realized the position was hopeless and surrendered to Commandant Piet Cronjé

Pieter Arnoldus "Piet" Cronjé (4 October 1836 – 4 February 1911) was a South African Boer general during the Anglo-Boer Wars of 1880–1881 and 1899–1902.

Biography

Born in the Cape Colony but raised in the South African Republic, ...

. The raiders were taken to Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

and jailed.

Aftermath

The Boer government later handed the men over to the British for trial and the British prisoners were returned to London. A few days after the raid, the Kaiser of Germany sent a telegram (the "Kruger telegram The Kruger telegram was a message sent by Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II to Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, president of the Transvaal Republic, on 3 January 1896. The Kaiser congratulated the president on repelling the Jameson Raid, a sortie by 600 ...

") congratulating President Kruger and the Transvaal government on their success "without the help of friendly powers", alluding to potential support by Germany. When this was disclosed in the British press, it raised a storm of anti-German feeling. Dr. Jameson was lionised by the press and London society, inflamed by anti-Boer and anti-German feeling and in a frenzy of jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

. Jameson was sentenced to 15 months for leading the raid, which he served in Holloway. The Transvaal government was paid almost £1 million in compensation by the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

.

For conspiring with Jameson, the members of the Reform Committee (Transvaal) The Reform Committee was an organisation of prominent Johannesburg citizens which existed late 1895/early 1896.

History

The Transvaal gold rush had brought in a considerable foreign population, chiefly British although there were substantial mi ...

, including Colonel Frank Rhodes and John Hays Hammond

John Hays Hammond (March 31, 1855 – June 8, 1936) was an American mining engineer, diplomat, and philanthropist. He amassed a sizable fortune before the age of 40. An early advocate of deep mining, Hammond was given complete charge of Ce ...

, were jailed in deplorable conditions, found guilty of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, and sentenced to death by hanging. This sentence was later commuted to 15 years’ imprisonment, and in June 1896, all surviving members of the Committee were released on payment of stiff fines. As further punishment for his support of Jameson, the highly decorated Col. Rhodes was placed on the retired list by the British Army and barred from active involvement in army business. After his release from jail, Colonel Rhodes immediately joined his brother Cecil and the British South Africa Company in the Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the Matabeleland Rebellion or part of what is now known in Zimbabwe as the First ''Chimurenga'', was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region later known as Southern Rhodesia, now modern-day Zimbabwe. ...

taking place just north of the Transvaal in Matabeleland. Cecil Rhodes was forced to resign as Prime Minister of Cape Colony in 1896 due to his apparent involvement in planning and assisting in the raid; he also, along with Alfred Beit

Alfred Beit (15 February 1853 – 16 July 1906) was a Anglo-German gold and diamond magnate in South Africa, and a major donor and profiteer of infrastructure development on the African continent. He also donated much money to university edu ...

, resigned as a director of the British South Africa Company.

Jameson's raid had depleted Matabeleland of many of its troops and left the whole territory vulnerable. Seizing on this weakness, and a discontent with the British South Africa Company, the Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe and Botswana

Languages

* Southern Ndebele language, the language of the South Ndebele

*Northern Ndebele language

Northern ...

revolted during March 1896 in what is now celebrated in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

as the First War of Independence, the First Chimurenga

''Chimurenga'' is a word in the Shona language. The Ndebele equivalent, though not as widely used since the majority of Zimbabweans are Shona speaking, is ''Umvukela'', meaning "revolutionary struggle" or uprising. In specific historical terms ...

, but it is better known to most of the world as the Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the Matabeleland Rebellion or part of what is now known in Zimbabwe as the First ''Chimurenga'', was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region later known as Southern Rhodesia, now modern-day Zimbabwe. ...

. The Shona

Shona often refers to:

* Shona people, a Southern African people

* Shona language, a Bantu language spoken by Shona people today

Shona may also refer to:

* ''Shona'' (album), 1994 album by New Zealand singer Shona Laing

* Shona (given name)

* S ...

joined them soon thereafter. Hundreds of European settlers were killed within the first few weeks of the revolt and many more would die over the next year and a half. With few troops to support them, the settlers had to quickly build a laager

A wagon fort, wagon fortress, or corral, often referred to as circling the wagons, is a temporary fortification made of wagons arranged into a rectangle, circle, or other shape and possibly joined with each other to produce an improvised militar ...

in the centre of Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council cl ...

on their own. Against over 50,000 Ndebele held up in their stronghold of the Matobo Hills

The Matobo National Park forms the core of the Matobo or Matopos Hills, an area of granite kopjes and wooded valleys commencing some south of Bulawayo, southern Zimbabwe. The hills were formed over 2 billion years ago with granite being forced ...

the settlers mounted patrols under such people as Burnham, Baden-Powell

Lieutenant-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, ( ; (Commonly pronounced by others as ) 22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army officer, writer, founder and first Chief Scout of the wor ...

, and Selous. It would not be until October 1897 that the Ndebele and Shona would finally lay down their arms.

Political impact

In Britain the Liberal Party objected to, and later opposed, the Boer War. Later, Jameson became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony (1904–08) and one of the founders of the Union of South Africa. He was made abaronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in 1911 and returned to England in 1912. On his death in 1917, he was buried next to Cecil Rhodes and the 34 BSAC soldiers of the Shangani Patrol

The Shangani Patrol (or Wilson's Patrol) was a 34-soldier unit of the British South Africa Company that in 1893 was ambushed and annihilated by more than 3,000 Matabele warriors in pre-Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), during the First Matab ...

(killed in 1893 in the First Matabele War

The First Matabele War was fought between 1893 and 1894 in modern-day Zimbabwe. It pitted the British South Africa Company against the Ndebele (Matabele) Kingdom. Lobengula, king of the Ndebele, had tried to avoid outright war with the company ...

) in the Matobos Hills, near Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council cl ...

.

Effect on Anglo-Boer relations

The affair brought Anglo-Boer relations to a dangerous low. Tensions were further exacerbated by the "Kruger telegram The Kruger telegram was a message sent by Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II to Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, president of the Transvaal Republic, on 3 January 1896. The Kaiser congratulated the president on repelling the Jameson Raid, a sortie by 600 ...

" from the German, Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

congratulating Kruger on defeating the "raiders". The German telegram came to be widely interpreted as an offer of military aid to the Boers. Wilhelm was already perceived by many as anti-British after initiating a costly naval arms race between Germany and Britain.

As tensions quickly mounted, the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

began importing large quantities of arms and signed an alliance with the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

in 1897. Jan C. Smuts

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. I ...

wrote in 1906 of the Raid, "The Jameson Raid was the real declaration of war... And that is so in spite of the four years of truce that followed... heaggressors consolidated their alliance... the defenders on the other hand silently and grimly prepared for the inevitable."

Joseph Chamberlain condemned the raid despite previously having approved Rhodes' plans to send armed assistance in the case of a Johannesburg uprising. In London, despite some condemnation by the print-media, most newspapers used the episode as an opportunity to whip-up anti-Boer feelings. Though they faced criminal charges in London for their actions in South Africa, Jameson and his raiders were treated as heroes by much of the popular public. Chamberlain welcomed the escalation by Transvaal as an opportunity to annex the Boer states.

Modern reactions

To this day, Jameson's involvement in the Jameson Raid remains something of an enigma, being somewhat out-of-character with his prior history, the rest of his life and successful later political career. In 2002, TheVan Riebeeck Society

Historical Publications Southern Africa (HiPSA) is a South African text publication society which publishes or republishes primary sources relating to southern African history. It was founded in 1918 as the Van Riebeeck Society for the Publicati ...

published Sir Graham Bower's ''Secret History of the Jameson Raid and the South African Crisis, 1895–1902'' (edited by Deryck Schreuder and Jeffrey Butler, Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, Second Series No. 33), adding to growing historical evidence that the imprisonment and judgement upon the Raiders at the time of their trial was unjust, in view of what has appeared, in later historical analysis, to have been the calculated political manoeuvres by Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

and his staff to hide his own involvement and knowledge of the Raid.

In a 2004 review of Sir Graham Bower's account, Alan Cousins commented that "A number of major themes and concerns emerge" from Bower's history, "perhaps the most poignant being Bower’s accounts of his being made a scapegoat in the aftermath of the raid: 'since a scapegoat was wanted I was willing to serve my country in that capacity'."

Cousins writes of Bower that:

Finally, Cousins states that

See also

* Drifts Crisis *Military history of South Africa

The military history of South Africa chronicles a vast time period and complex events from the dawn of history until the present time. It covers civil wars and wars of aggression and of self-defence both within South Africa and against it. It in ...

* Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

* Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the Matabeleland Rebellion or part of what is now known in Zimbabwe as the First ''Chimurenga'', was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region later known as Southern Rhodesia, now modern-day Zimbabwe. ...

Notes

Further reading

* * * * Holli, Melvin G. “Joseph Chamberlain and the Jameson Raid: A Bibliographical Survey.” ''Journal of British Studies'' 3#2 1964, pp. 152–166online

* A revision of * * Onselen, Charles van. ''The Cowboy Capitalist: John Hays Hammond, the American West, and the Jameson Raid''(University of Virginia Press, 2018), * * * * * {{Authority control 1895 in South Africa 1896 in South Africa 19th century in Africa African resistance to colonialism Conflicts in 1895 Conflicts in 1896 December 1895 events History of Pretoria History of the British Empire January 1896 events Military history of South Africa Military raids South Africa–United Kingdom relations Wars involving Botswana Wars involving the British South Africa Company Wars involving the South African Republic